We’ve just gotten through most of Jacob’s life. And Jacob is probably the most interesting character in the Tanach. His whole life, he wrestles with what’s for negotiable and what’s not. Let’s go through what happens to him (that’s interesting for this analysis)

Toldos

We see this, of course, when we’re introduced to him. He gets his name יעקב, when he, coming out from the womb right after his twin, holds him בעקב, in the heel, presumably trying to get out first (thereby earning the בכרה, the rights of the first born son). He’s already then stretching for more than he was destined too, not knowing it’s forbidden to him. (1 Mos 25:24-26)

We’re immediately thrown into the next scene, where Esav, Jacobs brother comes back from hunting and asks Jacob for (really plain) food. Jacob immediately seeks to benefit from his brother’s weak position and asks for his בכרה in order to serve him food. Esav replies, pretty harshly, הנה אנכי הולך למות ולמה־זה לי בכרה. I am going towards death, why would I need my בכרה? Esav then proceeds to sell the בכרה. The text here seems to tell us two things that interest us: 1) Jacob seems to think he can extort someone hungry on the verge of dying into paying overprice – for a bowl on lentils! 2) Jacob seems to think that the בכרה is something that can be traded, like a commodity. The text then tells us that Esav “despised” his בכרה by this, but truly, what can someone starving to death do. As a reader, we must ask if this is a valid trade. (1 Mos 25:29-34)

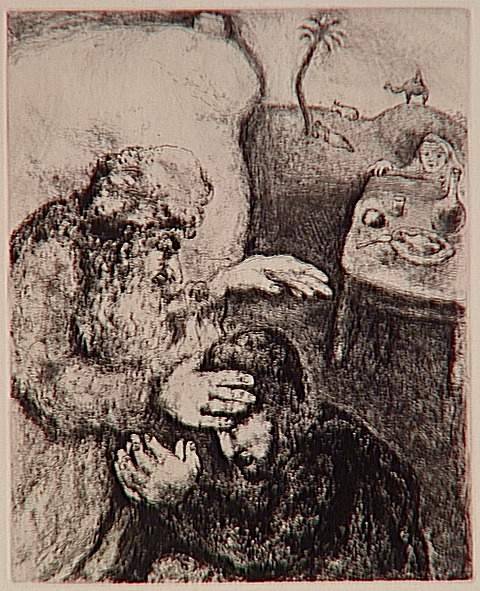

The next scene we see with the brothers is probably the most famous one: the one where Isaac is supposed to give the blessing of the בכרה to Esav, but Jacob (together with his mom, Rivke) manages to steal it with list. Jacob has several oppurtinities to confess to his crime, especially when he sees that Isaac doesn’t quite trust that it’s him. Esav discovers this just a bit too late, when Isaac has just given the blessing to Jacob. The Torah, often extremely economic in its wording, describes Esavs initial reaction as ויצעק צעקה גדלה ומרה עד מאד (and he cried out a large cry and was bitter exceedingly long-lasting) – six words when one would have been enough. He proceeds to say “הכי קרא שמו יעקב ויעקבני זה פעמים את בכרתי לקח” – was he called “Jacob” and he deceived me twice and took my birthright, using Jacobs name against him, redefining his identity. (1 Mos 27)

Isaacs reaction here might be confusing. When he learns he’s been tricked, he claims he can’t undo the blessing, even though it always belonged to Esav and Jacob only got it through deception. I can think of three explanations: 1) Isaac thinks his words when giving the blessing has some sort of magic power, maybe stemming from the blessing he (and Avrom once) got from God, 2) Isaac wanted, in his heart, for Jacob to have the blessing (it could be explained from 1 Mos 26:34-35) or 3) Isaac can see what Jacob needs from his parent. Lets delve into explanation 3.

Isaac has, through his later life, seen how Jacob uses lies and deception to get what he wants. He also sees how Jacobs mother, Isaacs wife, helps him. He knows that Rivke is plotting against Esav for Jacob to get the בכרה. He understands, as a wise parent, that he needs to be a damn good role model. And an important part of being a role model for Jacob is to no matter what stick to his word. He knows how badly Jacob needs to learn this quality, especially if he’s going to inherit.

Wajetsei

What happens next is that Jacob is sent to Padan-Aram, where his mothers family lives, to find a wife there. On his way there, he meets God in a dream, and is promised many offspring and protection, and even this he feels the need to barter. When he wakes up after this dream, he swears אם – if God protects me and so forth, the lord shall be his God. (1 Mos 28:12-21)

He meets and kisses Rochel, and the Torah decides to even tell us that he cries in this moment. He makes a deal with Rochels father, Lavan, that he shall work seven years for her in order to get permission to marry her. He does so, but after the wedding night, he wakes up and sees he var deceived to marry not Rochel but the older sister Lea. He confronts Lavan who answers לא יעשׂה כן במקומנו לתת הצעירה לפני הבכירה – it’s not what we do in this place to give (up for marriage) the younger before the first born woman. בכירה is used, just as בכרה was used about Esav. If we didn’t pick up the analogy before, this certainly will help us see it. Lavan is here compared to the younger Jacob. Jacob then has to work seven more years to marry Rochel as well. (1 Mos 29)

Why doesn’t Lavan tell Jacob about this מנהג המקום, this local tradition? Why should he have to? Jacob wasn’t among strangers. He was among his mothers family. As Lavan tells him, אך עצמי ובשרי אתה, indeed you are my bones and flesh. Jacob must have known what the local tradition was, yet he tried to barter his way out of it. Jacob still can’t grasp that some things aren’t for sale.

Using his list once again, he barters his wages for when he takes leave of Lavan. He uses the knowledge he’s gained from being the actual working shepherd in the fields to get the best sheep from Lavans flocks. (1 Mos 30:25-43). He manages to leave Lavans grip and household, and Rochel managed to steal his idols during the escape, which they manage to hide from him when confronted with the theft, by Rochel (who has them in the saddle) claiming to be in דרך נשים, the way of women, having her period – and consequently can’t be searched. (1 Mos 31:34-35)

Wajishlach

Jacob now prepares to meet Esav again, knowing Esav might very well kill him. Jacob uses his list to prepare for every outcome. He sends loads of gifts, he prays to God, and he has a speech he gives to Esav when they meet, filled with humility. Yet, Jacob also clearly has a plan B, which is a military plan. Again, we kind of see a two-faced Jacob. (1 Mos 32:1-33:15)

Yet, Jacob does, for the first time, face his past deception with an attempt at truth. It is in this moment he faces the messenger of God who wrestles him and, when defeated, blesses him with the new name of Jisroel, because he has “wrestled with God and with people and proved capable”. Just like his identity was defined through his name when he deceived Isaac and Esav, his identity is defined yet again when he has the courage to face Esav again. (1 Mos 32:22-32)

In the next scene, Shchem, a local prince, sleeps with Jacobs daughter Dina, and asks to marry her. Jacob’s sons handle the negotiation. They ask Shchem to have himself and the whole city circumcised, and when they’re trying to heal after the operation, Jacob’s sons perform a massacre in the city as revenge for what Shchem did to Dina. Jacob himself is very passive in this whole scene. Only in the end does he even comment on the situation. He doesn’t defend or criticize what Shchem, Dina or Jacob’s sons did – his comment is purely strategic. (1 Mos 34)

We should also note what happens when Rochel, Jacob most loved wife, dies. The verse is one of the most well written in the Torah, in my opinion. She gives birth to another son. It says: ויהי בצאת נפשה כי מתה ותקרא שמו בן־אוני ואביו קרא לו בנימין, it happened when her last breath left her – whilst she was dying – that she called him ben oni (son of my sorrow, not surprising for the birth that killed her), but he (Jacob) called him ben jomin (son of my strenght). Jacob can’t even respect his wife’s last dying breath. (1 Mos 35:18)

Wajeishev

This parsha starts with וישב יעקב, and Jacob settled. As I’ve commented in the droshe I wrote for my ofruf-service, I think this must be understood through the explanation in Talmud Sanhedrin 106a:15:

אמר רבי יוחנן כל מקום שנאמר וישב אינו אלא לשון צער שנא’ (במדבר כה, א) וישב ישראל בשטים ויחל העם לזנות אל בנות מואב (בראשית לז, א) וישב יעקב בארץ מגורי אביו בארץ כנען ויבא יוסף את דבתם רעה אל אביהם ונאמר (בראשית מז, כז) וישב ישראל בארץ גשן ויקרבו ימי ישראל למות (מלכים א ה, ה) וישב יהודה וישראל לבטח איש תחת גפנו ותחת תאנתו (מלכים א יא, יד) ויקם ה’ שטן לשלמה את הדד האדומי מזרע המלך הוא באדום

Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Everywhere that it is stated: And he dwelt, it is nothing other than an expression of pain, of an impending calamity, as it is stated: “And Israel dwelt in Shittim, and the people began to commit harlotry with the daughters of Moab” (Numbers 25:1). It is stated: “And Jacob dwelt in the land where his father had sojourned in the land of Canaan” (Genesis 37:1), and it is stated thereafter: “And Joseph brought evil report of them to his father” (Genesis 37:2), which led to the sale of Joseph. And it is stated: “And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt in the land of Goshen” (Genesis 47:27), and it is stated thereafter: “And the time drew near that Israel was to die” (Genesis 47:29). It is stated: “And Judah and Israel dwelt safely, every man under his vine and under his fig tree” (I Kings 5:5), and it is stated thereafter: “And the Lord raised up an adversary to Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was of the king’s seed in Edom” (I Kings 11:14).

From the point of view of this text, we can understand וישב as in the yiddish word מישב זײַן, to be established in though. Jacob has grown from the young man he used to be, but has he learned his lesson, the lesson his father tried to teach him? Absolutely not. The story of Joisef teaches us that. Jacob has no problem at all with playing favorite with Joisef, even though he’s by far not the first born. Breishes Raba 84:8 tries to teach us this:

/…/ רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ בְּשֵׁם רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן עֲזַרְיָה אָמַר, צָרִיךְ אָדָם שֶׁלֹא לְשַׁנּוֹת בֵּן מִבָּנָיו, שֶׁעַל יְדֵי כְּתֹנֶת פַּסִּים שֶׁעָשָׂה אָבִינוּ יַעֲקֹב לְיוֹסֵף, (בראשית לז, ד): וַיִּשְׂנְאוּ אֹתוֹ /…/

/…/ Reish Lakish, in the name of R. Elazar ben Azaria said: One should not treat one of his sons differently, for because of the ksones pasim his father Jacob made for Joisef, they hated him. /…/

And Jacob’s sons, being their fathers children, deceives Jacob to think Joisef has been killed by a beast. Once again, Jacob’s deception comes around to bite him. He never learns, and he gets paid back for his deception several times. His children don’t seem to learn either. Except for, I would claim, Joisef, but that’s another text.

Peiresh

What should we learn from Jacobs life, then? That not everything is for sale, first of all. Our laws and our traditions are not for sale. Our integrity and truth are not for sale. Some things can’t be bartered. This is true in religious matters and laws, and in secular matters and laws. It teaches us that contributing to a society of deception comes around to bite us (in a less dramatic way than Kant’s explanation).

What are not for sale? Food for the hungry aren’t for sale. If we can feed another person, we should. Our institutions aren’t for sale. A lesson that needs to be learned in the kinds of liberal democracies built by ads and PR firms, by well financed think tanks and lobby organisations.

And it teaches us that our actions define us, when we are acting in deceit but also when we repent. Jacob (and his family) is caught in habit, but Jisroel prevails.

Leave a Reply